“A double rainbow, all the way! What does it mean?!” (Paul Vasquez, in a viral YouTube video of 2010)

A famous pair of Greek maxims inscribed over the entrance to the Temple of Apollo at Delphi urged visitors to nurture self knowledge and to exercise restraint: “Know thyself. Nothing too much.” This advice is helpful for just about every human endeavor, but it applies especially well in photography. The more that we are in touch with our own ideas and interests, the more able we are to make creative decisions that are fruitful. Good inner guidance can avoid a lot of common excesses that tend to stymie creative development, such as relying too much on standard practice or becoming too dependent on limiting habits. One common habit that can be especially limiting in landscape photography is putting too much emphasis on locations and not enough on our relationships with them.

What follows is essentially a guide to photographing landscapes rather than locations—a look at what makes land and nature meaningful and what is at stake in misplacing our values on geographical points. After explaining why these distinctions are important for both creativity and conservation, I offer a set of seven tips for creating more personally expressive photographs.

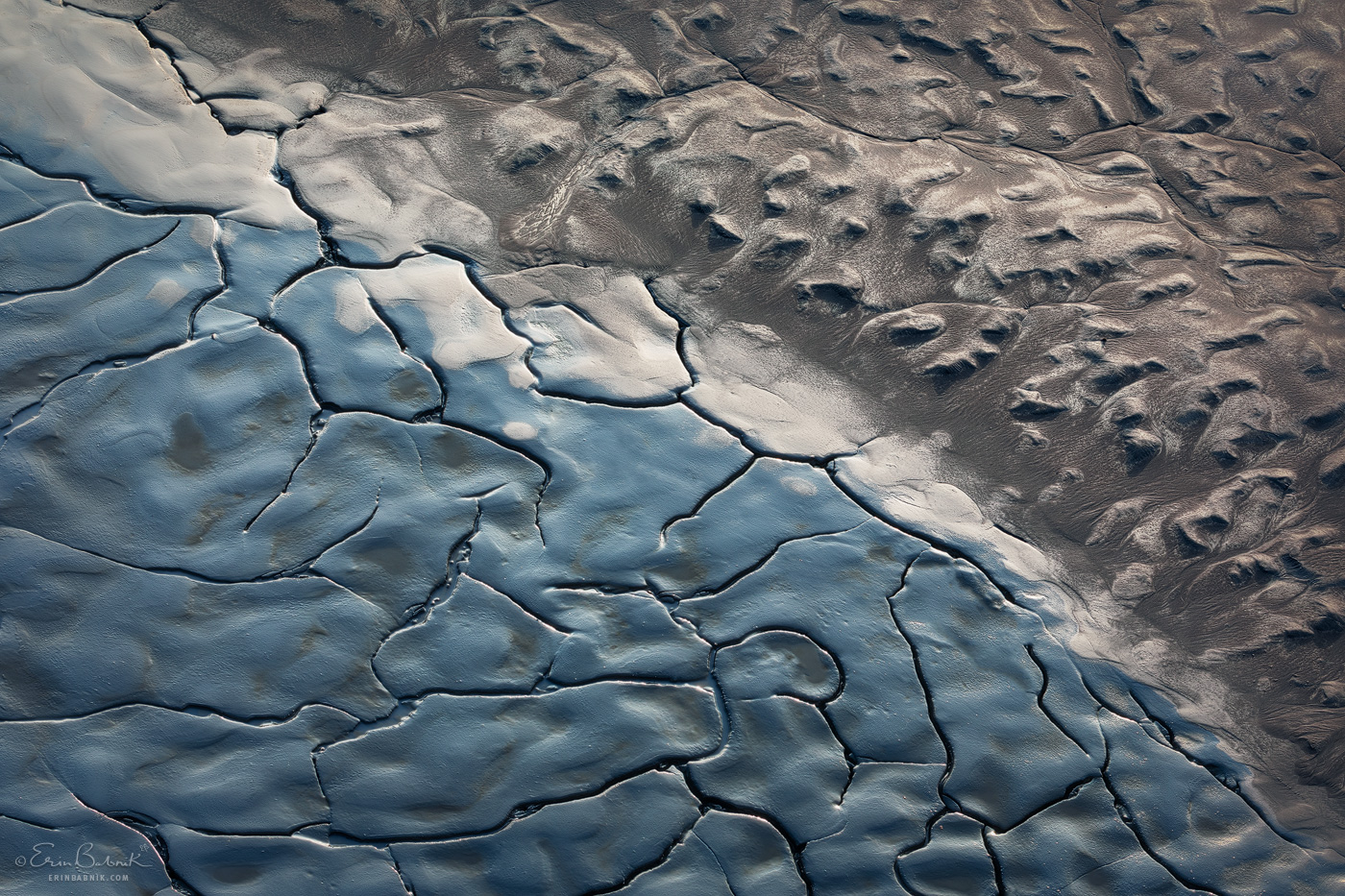

“Catharsis” by Erin Babnik, French Alps (2017). CLICK PHOTO TO ENLARGE. My fascination with atmosphere extends to scenes that remind me of it, including this one, which recalls the appearance of low storm clouds catching the sun. In my mind, the turbulence of the action and the dramatic play of light and shadow combine to suggest a cathartic release, a hopeful breakthrough from turmoil into enlightenment.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The Trouble with Locations

What is a Landscape?

Useful Approaches in the Field and Beyond (7 Tips)

The Trouble with Locations

Landscape photographers tend to be quite passionate about locations. After all, our photographs have to start with an excursion to somewhere, no matter how abstract, avant-garde, or unrecognizable our results might be. Therefore, locations often give structure to our efforts. We speak of location “bucket lists”, we create location galleries, we produce books about locations, and we continually revisit famous vantage points like devoted pilgrims. At the extremes, we fetishize beautiful locations as commodities to be collected or even conquered. For better or for worse, locations typically define the genre. Indeed, up until about the last decade, it was customary for landscape photographers to title their photos simply with location names.

Of course the areas that we visit are special to us, and choosing to visit them is part of the creative process. Nonetheless, specifically trying to showcase a location can derail the imagination quite easily. For example, if we fixate on the marquee features of an area, opportunities that omit them may escape our notice, and we are likely to find only what we already know to be there. I’ll never forget the morning that I watched a group of photographers remain glued to where they had set up their tripods to catch a sunstar under a sandstone arch on a morning when the entire region was shrouded in dense cloud cover. Not only was there no hope of seeing the sun under the arch (or seeing anything other than flat light on it), but unusual opportunities for photographing cloud inversions were on offer from a vantage point about a hundred feet away. Those alternative views would not emphasize the area’s most famous landmark however, and so most of the photographers in attendance took no interest in them. Meanwhile, everyone who photographed the misty canyon came away with something quite special and probably more personally rewarding.

Photographing a famous view does not necessarily switch off the imagination, of course. Even photographs that depict an icon of nature can make a place seem delightfully strange again, but the ‘special something’ that makes the difference rarely comes about on its own. As many examples attest, very unique locations and conditions can appear quite unimpressive in a photograph that does them no justice. What causes a photo to be especially compelling is usually a photographer’s ideas manifested through creative decisions. It’s the photographer’s imagination that elevates a landscape by making it especially expressive—and perhaps even more beautiful than the casual observer may see it.

“Ripple” by Erin Babnik, Death Valley National Park (2018). CLICK PHOTO TO ENLARGE. The surreality of badlands always ignites my imagination, and I enjoy wandering around in them to see how their forms present themselves to me from different angles. The rhythm and flow of the stripes and folds in this particular scene give a lot of motion to it, reminding me that these features truly are in motion, albeit at a pace much slower than what a human can observe in one visit.

“Tailwind” by Erin Babnik, Italian Dolomites (2018). CLICK PHOTO TO ENLARGE. On this very memorable morning the sun was able to shine behind the atmosphere just at the moment when all of the grand forms flanked one of my favorite peaks in this area, making it look like a sailboat or a figure arching its back while being pushed through space.

Fixating on locations can complicate the protection of those places as well. There has been a lot of discussion lately about the role that landscape photography plays in compounding problems of over-visitation in many areas by directing traffic to them. Our culture of location emphasis is not wholly to blame, but it certainly fuels the fire by placing the highest value on geographical points, implicitly giving locations most of the credit for the allure of landscape photographs. So naturally anyone who believes that message will covet locations, just as some people covet whatever gear seems to hold some magic promise. Alternatively, we could have a culture of creativity, one that gives priority to celebrating ideas about nature as a whole, about our own experiences within wild environments, about personal growth through travel, about the human condition, about personal expression, about beauty, or about any number of emphases that put the focus somewhere other than on a set of coordinates.

Why is it that a fire at Notre-Dame cathedral can bring in immediate and substantial private financial donations, whereas national parks can suffer for weeks as restrooms continuously overflow with trash and visitors’ waste during a government shutdown? The disparity is at least partly due to a pervasive modern tendency to view nature in opposition to humanity. The “man versus nature” mentality positions the latter as neither connected to us nor created by us, and therefore it reduces nature to an external resource that can be possessed and exploited. We aren’t doing nature any favors by promoting the notion that locations on their own are more important than the relationships that we have with them. In other words, landscape photographs should be celebrated as the products of collaborations with nature rather than being presented as mere “captures” of it. The photographer is a ‘maker’ too.

“Whirlwind” by Erin Babnik, Icelandic Highlands (2018). CLICK PHOTO TO ENLARGE. During a second visit to this lake, my group had completely different conditions to work with, and the volcano across the lake was fully revealed. Gone were the rain and the mist, and gone with them were the mystery and the magic. Although I photographed this composition again on that second visit, it was this first outing with the thick weather that most captured my imagination.

What is a Landscape?

The term ‘landscape’ has broad applications for anyone willing to ponder them. Aside from the typical idea of a sweeping outdoor vista, there are many types of scenes that might be considered landscapes. So-called “small scenes”, “intimates”, or even macro studies can signify or resemble larger realms, so they are rightful variants in the genre of landscape photography. For that matter, it may not even be necessary for a photograph that suggests ideas about land and nature to show any outdoor elements at all. The much celebrated British landscape photographer John Blakemore made this point about a series of photographs that he created in his seventies, after he began to travel less and turned his camera toward views that he could find right within his own house. He spent ten years photographing his living room, thinking of it as a sort of natural habitat. In summarizing his thoughts about this series, he said, “Should we allow these [scenes] as a certain sort of domestic landscape? I think we should.”

Simply put, a landscape is a mental construct. It’s a space made up of ideas about land and nature, while locations are simply the spaces between certain coordinates. Landscape photographs, therefore, are much more than simple records of some geographical features. At their most descriptive they may come close to being mere visual summaries, but at their most suggestive, they are loaded with potential for interpretation. Because they can contain both settings and subjects, landscapes are akin to a stage show and are especially good at signifying the universal human experiences that we tend to associate with a good drama, such as emotions or interpersonal relationships. In addition, they commonly gain potency from local myths and allegories that linger in a culture’s collective memories.

“Trajectory” by Erin Babnik, Italian Dolomites (2017). CLICK PHOTO TO ENLARGE. The way that the light cut a swath through this scene made the illuminated limestone look to me like a giant comet more so than a mountain. Although there was a very recognizable and well known peak visible just out of the frame, I was far more interested in the abstract quality of this view.

The particular memories that people might associate with landscapes will depend upon their individual experiences, but we all have ingrained notions of some sort. For example, the expansiveness of the American west is wrapped up with the concept of freedom for most westerners, and mountains exist in the mythologies of most cultures as places that are close to the gods. None of these associations are inevitable, but there are always associations, traditions, and perceptions that will factor into a person’s impressions of landscapes. As Simon Schama explains,

The “cathedral grove,” for example, is a common tourist cliché [about] the old growth forests of the Pacific Northwest. But beneath the commonplace is a long, rich, and significant history of associations between the pagan primitive grove…and the distinctive forms of Gothic architecture. (Landscape and Memory)

The “cathedral grove,” for example, is a common tourist cliché [about] the old growth forests of the Pacific Northwest. But beneath the commonplace is a long, rich, and significant history of associations between the pagan primitive grove…and the distinctive forms of Gothic architecture. (Landscape and Memory)

“Down to Earth” by Erin Babnik, Eastern Sierra (2019). CLICK PHOTO TO ENLARGE. I find ongoing fascination in the way that clouds can bring mystery and magic to a scene when they interact with a landscape very intimately. This incredibly distinct and low shelf of clouds scraped across a massive section of mountains, blanketing all but the lowest foothills and pressing up against them as if in a gesture of protection.

Ultimately, any landscape photograph is only ever ‘about’ whatever comes to mind for the photographer or the viewer, and there may be little overlap between what the first intends and the other understands. Nonetheless, the slippery quality of that space between intention and reception does not render photographs meaningless. The open-endedness of visual communication is one of its great powers, providing the potential for a single photograph to have a wide range of meaning. For example, a photo of a forest hanging in the contemplative space of a museum might inspire a very different set of thoughts than it would while hanging in the lobby of a lumber company’s headquarters. So although we can never really pin down a single message for any given photo, the potential for meaning is always there for us to explore.

Similarly, a photo can ‘speak’ differently to viewers depending on what we have to say about them. Titles of photographs are especially suggestive in this regard, having the potential to direct attention away from strictly geographical concerns, transporting viewers into that rich thought-world of associations that transcends whatever particular soil, stone, or blossoms made an impression on a camera’s sensor. Whereas a straightforward location identifier, such as “Mesa Arch at Sunrise”, may pique curiosity about travel to that location, choosing a metaphorical or poetic title (“Steady Ascent”, let’s say) could prompt a person to dream about life goals instead. (Personally, I’d rather risk choosing a title that might seem a bit trite over one that sounds indifferent.)

“Pas de Deux” by Erin Babnik, Italian Dolomites (2018). CLICK PHOTO TO ENLARGE. The elegance of this low mist and the appearance of intimacy between the two peaks combined for me to suggest a couple of dancers, one leaning in to the other during the height of their performance. Such visions can be quite personal and may never occur to anyone but the photographer. Viewers may see something else entirely, but that is the beauty of art’s open-endedness.

Useful Approaches in the Field and Beyond (7 Tips)

If you have read this far, then you may be wondering if there is a distinct set of criteria that characterize a preoccupation with locations and how to move beyond them. Aside from titles, captions, and other presentational choices, no part of a photographer’s message can ever be absolute; so the short answer is no, there is no litmus test to determine the expressiveness of a photograph. Nonetheless, there are some steps that you can take to try to pour more of your own self into your photos. The following suggestions are starting points for thinking in terms of landscapes rather than locations.

- Embrace the imperceptible. Some of the most compelling landscape photos are those that hide as much as they show. Atmosphere, framing, darkness, and focus are all among the variables that can create a sense of mystery or poetry about the landscapes that we feature rather than making a location merely identifiable.

- Embrace the unpredictable. Some landscapes are always changing and are characterized by variety more than anything else. Dune fields, forests, desert playas, glaciers, and areas that get a lot of dense atmosphere are all examples of landscapes that tend to produce endless varieties of photographs because they change so frequently. These are the kinds of places where the actual forms of the land can appear very different each time that you visit, and you can never really predict what might present itself to you. Consequently, these are the sorts of situations in which obvious vantage points are rare, meaning that there will always be a challenge in finding a composition and therefore a great opportunity to see one that presents itself through your own sensibilities.

- Explore further. If you tend to visit ‘brand name’ locations habitually, then it could be a good change of pace to head for some ‘blank’ places on the map—those areas where nothing is already named and promoted as a point of interest. Such places can be as small as a roadside pull-out or as large as an entire region. Rather than looking for landmarks, just look for the sake of seeing what you might find.

- Start with the light rather than the landmarks. If you want to produce a descriptive photo of a location, then it makes sense to think first of the features that define it and wait for whatever quality of light will define those features. Otherwise, the reverse process is more fruitful: look first at areas where interesting light is striking at any given moment and watch to see what it reveals. Starting with whatever light is available can produce a photo that may not give a strong sense of location but that is nonetheless very compelling. In the latter approach, you are more likely to invoke your own particular powers of observation, seeing something that another photographer might not.

- Bring language into play. While you are still behind the camera, try thinking of words or phrases that relate to what you are seeing, experiencing, or feeling. You may even think of them as possible titles for the photograph that you are creating. Word play will not always mesh well with visual thinking, but sometimes it can help to grease the wheels of personal expression by giving more weight to your own thoughts about what you are photographing.

- Give some thought to your titles. Location labels are sometimes necessary for certain usages, but they often end up as the titles of photographs or collections merely as a default choice, a thoughtless option that saves time and mental energy. It is certainly an extra step to decide on a meaningful title instead of choosing a practical one, and so a location title can be an expedient choice. Titling is a facet of presentation, however, and it is an opportunity to signal that a photograph is intended to be more than just a representation of a location. Perhaps more importantly, the exercise of titling a photograph forces a photographer to consider what gives each image its power and what each contributes to a collection or portfolio.

- Consider organizing photographs by themes. If you decide to present your photographs in collections rather than individually, consider a thematic unity rather than simply creating a set from a single trip or location. What unifying threads are running through your work besides regional proximity?

“Over the Wall” by Erin Babnik, French Alps (2018). CLICK PHOTO TO ENLARGE. Although the tallest of these cascades drops about 250 feet, there is nothing in the frame to give away the scale of them. Without that frame of reference, the scene becomes less about any particular location and more about the various ideas that water carving into rock can suggest.

“High Tide” by Erin Babnik, Icelandic Highlands (2018). CLICK PHOTO TO ENLARGE. The sky with some approaching clouds cast a reflection in a thin layer of standing water, making this patch of mud appear to be blue and white where the mud was most reflective. Just seconds after I noticed the colorful reflection, the clouds covered the area and turned it all white. I enjoyed how this scene reminded me of surf pounding against a mountainous shoreline. It’s wonderful to find “small scenes” that evoke grand landscapes.

Of course there will always be needs for photographs and projects that deal with the specific and objective details of particular locations. Guide books, magazine features, and local campaigns will always have their place in the world. Most of the time, however, a focus on locations is more of a default than a necessity. The choices that we make have implications for the creative process and for the awareness that we create about what we value, so it is important to choose thoughtfully. From planning through to presentation, we have many options available for expressing our ideas and for directing attention to them.

Erin Babnik is known internationally as a leading photographic artist, educator, and speaker, and she is honored to be a Canon Explorer of Light. Immersion in the visual arts has been the one constant in Erin’s life, including an extensive background in various visual media and a doctoral education in the History of Art. She is based out of offices in Europe and California and travels widely for workshops and speaking engagements. She is also known for her love affair with all things purple. | Erin’s Website: www.erinbabnik.com

Recent Comments